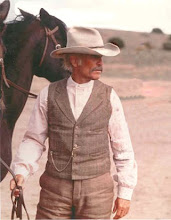

Charles Goodnight, Goodnight, Texas

Oliver Loving, Senior, is undoubtedly the first man who ever trailed cattle from Texas. His earliest effort

CHAS. GOODNIGHT

was in 1858 when he took a herd across the frontier of the Indian Nation or "No Man's Land," through eastern Kansas and northwestern Missouri into Illinois. His second attempt was in 1859; he left the frontier on the upper Brazos and took a northwest course until he struck the Arkansas River, somewhere about the mouth of the Walnut, and followed it to just about Pueblo, where he wintered.

In 1866 he joined me on the upper Brazos. With a large herd we struck southwest until we reached the Pecos River, which we followed up to Mexico and thence, to Denver, the herd being closed out to various posts and Indian reservations.

In 1867 we started another herd west over the same trail and struck the Pecos the latter part of June. After we had gone up this river about one hundred miles it was decided that Mr. Loving should go ahead on horseback in order to reach New Mexico and Colorado in time to bid on the contracts which were to be let in July, to use the cattle we then had on trail, for we knew that there were no other cattle in the west to take their place.

Loving was a man of religious instincts and one of the coolest and bravest men I have ever known, but devoid of caution. Since the journey was to made with a one-man escort I selected Bill Wilson, the clearest headed man in the outfit, as his companion.

Knowing the dangers of traveling through an Indian infested country I endeavored to impress on these men the fact that only by traveling by night could they hope to make the trip in safety.

The first two nights after the journey was begun they followed my instructions. But Loving, who detested night riding, persuaded Wilson that I had been overcautious and one fine morning they changed their tactics and proceeded by daylight. Nothing happened until 2 o'clock that afternoon, when Wilson who had been keeping a lookout, sighted the Comanches heading toward them from the southwest. Apparently they were five or six hundred strong. The men left the trail and made for the Pecos River which was about four miles to the northwest and was the nearest place they could hope to find shelter. They were then on the plain which lies between the Pecos and Rio Sule, or Blue River. One hundred and fifty feet from the bank of the Pecos this bank drops abruptly some one hundred feet. The men scrambled down this bluff and dismounted. They hitched their horses (which the Indians captured at once) and crossed the river where they hid themselves among the sand dunes and brakes of the river. Meantime the Indians were hot on their tracks, some of them halted on the bluff and others crossed the river and surrounded the men. A brake of carrca, or Spanish cane, which grew in the bend of the river a short distance from the dunes was soon filled with them. Since this cane was from five to six feet tall these Indians were easily concealed from view of the men; they dared not advance on the men as they knew them to be armed. The Indian on the bluff, speaking in Spanish, begged the men to come out for a consultation. Wilson instructed Loving to watch the rear so they could not shoot him in the back, and he stepped out to see what he could do with them. Loving attempting to guard the rear was fired on from the cane. He sustained a broken arm and bad wound in the side. The men then retreated to the shelter of the river bank and had much to, do to keep the Indians off.

Toward dawn of the next day Loving, deciding that he was going to die from the wound in his side, begged Wilson to leave him and go to me, so that if I made the trip home his family would know what had become of him. He had no desire to die and leave them in ignorance of his fate. He wished his family to know that rather than be captured and tortured by the Indians, he would kill himself. But in case he survived and was able to stand them off we would find him two miles down the river. He gave him his Henry rifle which had metallic or waterproof cartridges, since in swimming the river any other kind would be useless. Wilson turned over to Loving all of the pistols—five—and his six-shooting rifle, and taking the Henry rifle departed. How he expected to cross the river with the gun I have never comprehended for Wilson was a one armed man. But it shows what lengths a person will attempt in extreme emergencies.

It happened that some one hundred feet from their place of concealment down the river there was a shoal, the only one I know of within 100 miles of the place. On this shoal an Indian sentinel on horseback was on guard and Wilson knew this. The water was about four feet deep. When Wilson decided to start he divested himself of clothing except underwear and hat. He hid his trousers in one place, his boots in another and his knife in another all under water. Then taking his gun he attempted to cross the river. This he found to be impossible, so he floated downstream about seventy-five feet where he struck bottom. He stuck down the muzzle of the gun in the sand until the breech came under water and then floated noiselessly down the river. Though the Indians were all around him he fearlessly began his "geta-way." He climbed up a bank and crawled out through a cane brake which fringed the bank, and started out to find me, bare-footed and over ground that was covered with prickly pear, mesquite and other thorny plants. Of course he was obliged to travel by night at first, but fearing starvation used the day some, when he was out of sight of the Indians.

Now Loving and Wilson had ridden ahead of the herd for two nights and the greater part of one day, and since the herd had lain over one day the gap between us must have been something like one hundred miles.

The Pecos River passes down a country that might be termed a plain, and from one to two hundred miles there is not a tributary or break of any kind to mark its course until it reaches the mouth of the Concho, which comes up from the west, where the foothills begin to jut in toward the river. Our trail passed just around one of these hills. In the first of these hills there is a cave which Wilson had located on a prior trip. This cave extended back into the hill some fifteen or twenty feet and in this cave Wilson took refuge from the scorching sun to rest. Then he came out of the cave and looked for the herd and saw it coming up the valley. His brother, who was "pointing" the herd with me, and I saw him at the same time. At sight both of us thought it was an Indian as we didn't suppose that any white man could be in that part of the country. I ordered Wilson to shape the herd for a fight, while I rode toward the man to reconnoiter, believing the Indians to be hidden behind the hills and planning to surprise us. I left the trail and jogged toward the hills as though I did not suspect anything. I figured I could run to the top of the hill to look things over before they would have time to cut me off from the herd. When I came within a quarter of a mile of the cave Wilson gave me the frontier sign to come to him. He was between me and the declining sun and since his underwear was saturated with red sediment from the river he made a queer looking object. But even when some distance away I recognized him. How I did it, under his changed appearance I do not know. When I reached him I asked him many questions, too many in fact, for he was so broken and starved and shocked by knowing he was saved, I could get nothing satisfactory from him. I put him on the horse and took him to the herd at once. We immediately wrapped his feet in wet blankets. They were swollen out of all reason, and how he could walk on them is more than I can comprehend. Since he had starved for three days and nights I could give him nothing but gruel. After he had rested and gotten himself together I said :

"Now tell me about this matter."

"I think Mr. Loving has died from his wounds, he sent me to deliver a message to you. It was to the effect that he had received a mortal wound, but before he would allow the Indians to take him and torture him he would kill himself, but in case he lived he would go two miles down the river from where we were and there we would find him."

"Now tell me where I may find this place," I said. Then he proceeded to relate the story I have just given, of how they left the Rio Sule or Blue River, cutting across to the Pecos, how the Indians discovered them and how they sought shelter from them by hiding in the sand dunes on the Pecos banks; how Loving was shot and begged Wilson to save himself and to tell his (Loving's) family of his end ; how Wilson took the Henry rifle and attempted to swim but gave it up, as the splashing he made would attract the Indian sentinel stationed on the shoal.

Then Wilson instructed me how to find his things. He told me to go down where the bank is perpendicular and the water appeared to be swimming but was not. "Your legs will strike the rifle," he said. I searched for his things as he directed and found them every one, even to the pocket knife. His remarkable coolness in deliberately hiding these things, when the loss of a moment might mean his life, is to me the most wonderful occurrence I have ever known, and I have experienced many unusual phases of frontier life.

This is as I get it from memory and I think I am correct, for though it all happened fifty years ago, it is printed indelibly in my mind.

Thursday, June 18, 2009

Subscribe to:

Post Comments (Atom)

No comments:

Post a Comment