Hi Kelly,

Thank you for your interest in the Lonesome Dove Reunion; we hope to set a new date as soon as we see some improvement in the economy. Everyone was disappointed that we had to postpone this year’s event, but it had become clear we weren’t going to generate the support necessary to achieve the kind of success and fundraising dollars we hoped to realize. We are confident that the support we’ve already generated will result in an even bigger and better celebration in the future!

I’ve added you to the email update list, so you’ll be among the first to hear when we go forward with our plans. You can also check back with us at http://www.thewittliffcollections.txstate.edu/ for updates as well as information on new Lonesome Dove merchandise. A special 20th anniversary edition of Bill Wittliff’s A Book of Photographs From Lonesome Dove will be available for purchase from the Collections later this summer.

Thanks again for your interest and understanding.

______________________________________

Valerie J. Anderson

Lonesome Dove Event Assistant

The Wittliff Collections

Southwestern Writers Collection

Southwestern & Mexican Photography Collection

Alkek Library | Texas State University-San Marcos

512.245.2313 | www.thewittliffcollections.txstate.edu

Friday, June 26, 2009

Thursday, June 25, 2009

Wednesday, June 24, 2009

Tuesday, June 23, 2009

I'm a little sad right now

THE 20TH ANNIVERSARY & CAST REUNION

The Lonesome Dove 20th Anniversary and Cast Reunion has been postponed. Today's economic challenges make it very difficult to secure suitable support to underwrite such a unique event and we've opted to save it for a future date.

Please know how much we appreciate your interest and apologize for any inconvenience our postponement may cause.

Check back periodically for updates about Lonesome Dove or send us your email address and we'll place you on a list for news about the event when it is rescheduled.

If you're in the neighborhood, please consider visiting the Wittliff Collections to see the Lonesome Dove exhibition on permanent view.

Monday, June 22, 2009

Friday, June 19, 2009

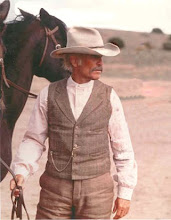

Ewing Galloway

As the last rays of sun sink past the horizon, the lone cowboy, a silhouette against a quickly dimming sky, slowly returns home in “Cowboy and Sunset”. Expressively preserving the beauty of a vanishing Western landscape, this photo proudly depicts the rugged, tradition-bound breed of men who live and work on it. From Ewing Galloway’s collection of striking, historical photographs, “Cowboy and Sunset” will stunningly complement Western décor.

Cindy Walker

Cindy Walker

Singer, Songwriter. What a face! Se wrote a song called bubbles in my beer which I need to find because what a great title. And she wrote you don't know me with Eddy Arnold which is a classic. Bing Crosby discovered her. And Willie has covered some of her tunes. A song called it's all your fault, which again I think is a really brilliant song title.

Thursday, June 18, 2009

SAN ANTONIO!

S.A. hosting 'Lonesome Dove's' 20th with stars galore

By

Jeanne Jakle

on Jan 13, 09 03:19 PM | Permalink | Comments (2)

LonesomeDoveposter.jpgCalling all "Lonesome Dove" fans! Here's something that could even beat, as Gus McCrae might put it, a good poke or swift kick to a pig:

San Antonio will be the setting for a meaty, star-studded, two-day celebration of the 20th anniversary of one of TV's most beloved and successful miniseries, "Lonesome Dove."

Among those expected to attend: the man who started it all, Pulitizer Prize-winning novelist Larry McMurtry, along with the man who turned the epic book into an Emmy-winning miniseries, Bill Wittliff.

In addition, principal cast members of the 1989 mini are expected to be on hand: Tommy Lee Jones, Robert Duvall, Anjelica Huston, Diane Lane, Chris Cooper, Danny Glover, Ricky Schroder and Glenne Headley.

Every dollar raised will benefit the extraordinary Wittliff Collections at Texas State University in San Marcos.

The celebration is a while off (Oct. 2 and 3), but you may want to mark your calendars, notify your relatives and save your pennies.

Events planned include a gala party, dinner and "Lonesome Dove" symposium in Trinity University's Laurie Auditorium that will consist of two separate panel discussions with actors from the miniseries.

There may even be a San Antonio Symphony concert built around "Lonesome Dove's" haunting and majestic music.

According to the event's contact, Beverly Fondren, several of the events, including the stellar panel discussions, will be open to the public and reasonably priced.

She also said the celebration is in real need of generous supporters and underwriters. For information on how to get involved, call Beverly at (512) 245-9058 or e-mail her at b.fondren@txstate.edu.

Another heads-up: A three-year traveling exhibition of "Lonesome Dove" photographs by Wittliff is being organized in conjunction with the anniversary celebration. Many of these wistful and dramatic images, such as this one of Duvall, robertduvall.jpgwill be on display at the Witte Museum from October through March 2010.The Wittliff Collections were founded by Texas native Wittliff and his wife, Sally. They are dedicated to furthering and preserving the very best of Texas and Southwestern culture.

Among the collections' holdings are the near-complete production archives for TV's "Lonesome Dove." These include original costumes, props, set designs, screenplay drafts and film dailies representing every printed take made on set.

For more information, go to www.thewittliffcollections.txstate.edu.

By

Jeanne Jakle

on Jan 13, 09 03:19 PM | Permalink | Comments (2)

LonesomeDoveposter.jpgCalling all "Lonesome Dove" fans! Here's something that could even beat, as Gus McCrae might put it, a good poke or swift kick to a pig:

San Antonio will be the setting for a meaty, star-studded, two-day celebration of the 20th anniversary of one of TV's most beloved and successful miniseries, "Lonesome Dove."

Among those expected to attend: the man who started it all, Pulitizer Prize-winning novelist Larry McMurtry, along with the man who turned the epic book into an Emmy-winning miniseries, Bill Wittliff.

In addition, principal cast members of the 1989 mini are expected to be on hand: Tommy Lee Jones, Robert Duvall, Anjelica Huston, Diane Lane, Chris Cooper, Danny Glover, Ricky Schroder and Glenne Headley.

Every dollar raised will benefit the extraordinary Wittliff Collections at Texas State University in San Marcos.

The celebration is a while off (Oct. 2 and 3), but you may want to mark your calendars, notify your relatives and save your pennies.

Events planned include a gala party, dinner and "Lonesome Dove" symposium in Trinity University's Laurie Auditorium that will consist of two separate panel discussions with actors from the miniseries.

There may even be a San Antonio Symphony concert built around "Lonesome Dove's" haunting and majestic music.

According to the event's contact, Beverly Fondren, several of the events, including the stellar panel discussions, will be open to the public and reasonably priced.

She also said the celebration is in real need of generous supporters and underwriters. For information on how to get involved, call Beverly at (512) 245-9058 or e-mail her at b.fondren@txstate.edu.

Another heads-up: A three-year traveling exhibition of "Lonesome Dove" photographs by Wittliff is being organized in conjunction with the anniversary celebration. Many of these wistful and dramatic images, such as this one of Duvall, robertduvall.jpgwill be on display at the Witte Museum from October through March 2010.The Wittliff Collections were founded by Texas native Wittliff and his wife, Sally. They are dedicated to furthering and preserving the very best of Texas and Southwestern culture.

Among the collections' holdings are the near-complete production archives for TV's "Lonesome Dove." These include original costumes, props, set designs, screenplay drafts and film dailies representing every printed take made on set.

For more information, go to www.thewittliffcollections.txstate.edu.

Lonesome Dove

20th Anniversary

By Tom Wilmes

It’s easy to see why many people relate to the story of Lonesome Dove as their own. In it they see their grandparents, or more abstractly the story of our country at the point its uniquely American character was laboring to be born. That the story is told so well is testament to the clear-eyed vision of Larry McMurtry as he penned his Pulitzer Prize-winning novel, and to the cast and crew who transcended the limits of television to bring his epic tale to the small screen with integrity intact. As the 20th anniversary of the Lonesome Dove miniseries approaches this February, we recognize it not only as the most successful miniseries of all time; we celebrate it as the first time anyone got the story right.

The seventh floor of the Albert B. Alkek Library on the Texas State University-San Marcos campus may seem like an unlikely destination for a pilgrimage, yet the devoted journey here from around the globe. They come to the Lonesome Dove room to view relics from a time and place that, if not quite sacred, is revered as an authentic expression of friendship, honor, and the hardships of the Old West as it really was.

Upon entering the room, visitors may feel like Call ticking through the journey in his mind at the end of the film. It’s a hell of a vision. The Hat Creek Cattle Company sign is prominently displayed, and is flanked by mannequins wearing the costumes of Augustus “Gus” McCrae and Woodrow F. Call, two former Texas Rangers who set out on one last adventure to establish the first cattle operation in Montana. Jake Spoon’s bandanna still contains traces of trail dust, and you can almost smell the despair in Lorena Wood’s much-distressed dress. Gus’ Colt Dragoon revolver is nearby, along with the arrows that killed him. The prop that was used for his body is a somber reminder of what was lost along the way, as is the cross from his grave and Deets’ headstone.

“It’s unusual to have so much documentation and memorabilia from a production,” says Steve Davis, assistant curator of the collection. “It’s a great example of how some of the magic of filmmaking is achieved.”

Davis says he’s seen visitors tear up at the site of Gus’ body, a few who have come dressed as Gus and Call, and one who even named his children after the two characters. More than a few people make the Lonesome Dove room their first stop on a journey to retrace the cattle drive route from Texas to Montana. Some do it on horseback.

“It’s heartwarming to work here and see the enormous number of people who come here—who make a pilgrimage, really— to be a part of the Lonesome Dove experience,” Davis says. “The reaction is the same from people from all over the world. There’s a common thread that unites—certainly people from Texas and the West feel that finally a Western told what it was really like. The film has struck a real chord in the American psyche.”

Tommy Lee Jones and Robert Duvall in Lonesome DoveLonesome Dove began as a movie idea dreamed up by Larry McMurtry. In 1972, McMurtry wrote a screenplay treatment titled Streets of Laredo to star John Wayne, Henry Fonda, and James Stewart. Peter Bogdanovich was to direct. When the project failed to gain traction, McMurtry expanded the story into a long, multi-layered novel. Published in 1985, the book grabbed the imagination of critics and the public alike, spending 20 weeks atop the New York Times best-seller list and winning the Pulitzer Prize for fiction.

“Streets of Laredo didn’t move forward because John Wayne wouldn’t do it,” McMurtry says. “He would have been the Call character in that story, and he didn’t want to play what he considered to be an unlikable, hard-ass character. When he wouldn’t do it, everyone else lost interest. I do have a family background that involved the cattle trade and trail drive tradition, which is probably the main reason I decided to write Lonesome Dove.”

Shortly before the novel’s publication, McMurtry sent a draft to Suzanne de Passe at Motown Productions. Motown optioned the film rights for $50,000 and CBS contracted to air Lonesome Dove as an eight-hour miniseries in four installments. All that remained was to find a way to adapt McMurtry’s sweeping novel for television. That’s when de Passe called on Bill Wittliff to write the screenplay. A Texas native like McMurtry, Wittliff felt a personal connection to the characters and events detailed in the novel.

“Like everybody I thought it was an astonishing piece of work,” Wittliff says. “From a personal response it was so much about my country, my people, but of course everybody felt that. That’s one of the great things about [the novel] Lonesome Dove, everybody identified with it, and I absolutely did.”

Wittliff , who was also co-executive producer with de Passe on the miniseries, wrote most of the screenplay during stints at his vacation home on South Padre Island. He would listen to the book on tape on the 6 1/2-hour drive from his home in Austin.

“What was wonderful about that is that I was driving, not writing, and as I was listening I was making the pictures in my head. I got to see the whole film, or my version of it, making those trips down to South Padre. I would stay a week or so and write, and then I’d drive back and that would be another 6 1/2 hours.”

From the beginning, Wittliff knew that in order for the miniseries to be a success, he had to remain true to the book, and include all of its interconnected threads and characters.

“It’s an epic story, and I never would have left out those subplots,” Wittliff says. “They just gave it the richness and the size. There were some things that we filmed that did not make it to the final edit because we just didn’t have time, but we squeezed in as much as we could.”

“Gus was my favorite character to play.”

— Robert Duvall

Even though the time schedule was almost as tight as the budget, it was soon apparent that the Lonesome Dove project was buoyed by an enthusiasm unlike anything in television. The buzz reached every corner of the industry.

“It’s Larry’s story that got ’em,” Wittliff says. “All the old clichés are true—like attracts in kind. It was a great book, it was a good script, and it attracted great artists. They were so taken by Larry’s novel. I mean we had people from all over the United States who drove in on their own nickel just to see if they could be extras. It wasn’t so much they wanted to get something out of it, they wanted to put something in.”

Diane Lane, who played Lorena Wood, remembers picking up on that feeling as soon as she arrived in Austin to begin filming. “Even the people I met at the airport and the people who did the driving were all so meticulously into each character,” she says. “I’d never seen anything like it.”

That groundswell of intense appreciation for McMurtry’s novel, published just a few years earlier, permeated every aspect of the miniseries.

“There was a reverence for the original material that was carried out by Bill in his writing of the screenplay,” Lane says. “There was also great care taken in the casting, and when [Robert Duvall] signed on everybody couldn’t wait to work with him, so we had top drawer people from the very get-go wanting to play every part.”

Tommy Lee Jones

“Every day was a complete joy. There’s a book called Crying for Daylight about Texas ranching culture, and that’s pretty much how we felt. You’d wake up early crying for daylight so you could get to work.”

— Tommy Lee Jones

Tommy Lee Jones, who played Call, says that the feeling among cast members was that the whole of Lonesome Dove was greater than the sum of its parts. “Everybody that worked on the film cared a great deal about the authenticity of it. They felt it was mainly their responsibility to do right by the book,” Jones says. “There was a social conscience at work that was unusual at that time in the world of television.”

Says Wittliff : “Everybody was absolutely dedicated to it. Nobody ever said ‘oh don’t worry about it, it’s just television.’ We knew it was television, but everybody’s attitude was ‘well, we’re making a huge, epic movie which as it happens is going to be shown on television.”

Epic is right. Shot over 16 weeks at three different locations, the project called for 89 speaking parts, as many as 600 head of cattle, 90 horses, and four sets of pigs. The conditions varied from 100-degree heat on set in Del Rio, Texas, where the fictional town of Lonesome Dove was constructed, to freezing rain and snow in Angel Fire, New Mexico.

The remote shooting locations, budget and time crunch, as well as the sheer scope of the project required an effort far beyond the pale of an average television shoot.

Lane recalls slogging through creeks with a wary eye out for cottonmouths, as well as finding a scorpion in her petticoat while filming the scene where Gus entices her into the river.

“It got larger than life, definitely larger than the scale of normal filmmaking,” Lane says. “But to be in the environs that the story takes place in was very affecting.”

Anjelica Houston and Robert Duvall

“I think it’s one of the best Westerns ever made. It’s about the land, men, women, animals, love, death, the American Dream, freedom, cruelty, fear, survival. And cowboys seem to love Clara.”

— Anjelica Huston

“I came in during the last three weeks and everyone was exhausted, having been in Texas and up in Angel Fire,” says Anjelica Huston, who played Clara Allen. “On several occasions I had to rally the troops because I could see the pages disappearing from the script—we simply did not have the time to do everything.”

But the motivation to bring the novel to life with the upmost authenticity, as well as the camaraderie of the cast and crew, overshadowed the numerous challenges.

We always said Lonesome Dove is the star, and I think everybody felt that,” Wittliff says. “Every once in a while the movie god just points through the clouds and says ‘regardless of what you do, this one’s going to work.’ There were so many places where this one could have fallen off the table. We were inventive in several places, but I don’t think any place cheated the film.”

Extraordinary luck also favored the production, such as when a freak snowstorm hit the community of Angel Fire in the middle of summer—on the same day the script called for a blizzard.

“We had snow machines and everything else ready to go and we woke up and the whole world was white,” Wittliff says. “Let me tell you, stuff like that happened all the time. The whole thing was like walking through a miracle.”

Diane Lane

“I was swayed into that relationship [with Robert Duvall in character as Gus] whether we were on camera or off in terms of our banter and cajoling around.”

— Diane Lane

The first installment of Lonesome Dove aired on Sunday, February 5, 1989. That day blasts of arctic air blew down from Canada and seized most of the country in its icy grip. Many people hunkered down in their homes to wait out the cold, and more than a few tuned in to CBS at 9 p.m. to watch Gus McCrae and Woodrow Call begin their adventure. Those who weren’t watching received a call from a friend or family member during the commercial breaks telling them to turn it on.

“Everybody stayed home and they started watching Lonesome Dove, and of course once you started then you couldn’t quit,” Wittliff says. “It was just unbelievable. People forget, at the time we did it the only thing deader than Westerns were miniseries, and this was a Western miniseries.”

Lonesome Dove generated huge ratings for CBS, and the network aired the miniseries for a second time shortly thereafter. Lonesome Dove won seven Emmys and two Golden Globes that year, but the public response was even more telling.

“It was overwhelming—the reviews were all great and the mail from people all across the country poured into the office,” Jones says. “We got heartfelt letters by the sack full from people who recognized their granddads and their fathers and their uncles in the story. They’d usually seen movies that were labeled ‘Western,’ and this seemed to defy that stereotype and be about real people and real places. They were very grateful to see the reality of their own history as opposed to some commercial distortion.”

Diane Lane

“The dialogue, the characters, the individualism of the people, the self-sufficiency, the ruggedness, it was all captured so well in Lonesome Dove,” says Ricky Schroder, who played Newt Dobbs. “It depicts a piece of our history as Americans that speaks to us. I think we all like to think about a time when life was simpler, when there was more black and white instead of gray.”

In many ways, Lonesome Dove also set a new benchmark for the way Westerns looked and felt. Says costume designer Van Broughton Ramsey: “I think that’s one of the reasons why we’re all still so proud of it 20 years later. Lonesome Dove was one of the first films to really show that the Old West is not about shoot ’em up, it’s about facing the everyday problems in life, being thankful for what you have, and moving on the best way you know how.”

It’s that simple, universal message, as well as the realistic portrayal of humanity in all its extremes, that keeps Lonesome Dove a fan favorite 20 years after its original release. And why, despite a lack of modern special effects and fast-paced sizzle, the film continues to resonate with a new generation of viewers.

“I wish Robert Urich [who played Jake Spoon] was still with us so he could experience the gratitude from all of the fans for his work,” says Lane. “But the wonderful gift of film is that the grave has no sway. You are forever in that encapsulated bubble and that’s a brilliant gift that film gives back to people who work in that medium. Your work can live forever.”

About the Photos

The photographs in this article were taken by Bill Wittliff during the production of Lonesome Dove. They are part of the Wittliff Collections at Texas State University-San Marcos, which Wittliff founded with his wife, Sally, in 1985. The photos are also collected in A Book of Photographs from Lonesome Dove published in 2007 by the University of Texas Press.

A Book of Photographs from Lonesome Dove

http://thewittliffcollections.txstate.edu/spec-coll/ldbook.htm

By Tom Wilmes

It’s easy to see why many people relate to the story of Lonesome Dove as their own. In it they see their grandparents, or more abstractly the story of our country at the point its uniquely American character was laboring to be born. That the story is told so well is testament to the clear-eyed vision of Larry McMurtry as he penned his Pulitzer Prize-winning novel, and to the cast and crew who transcended the limits of television to bring his epic tale to the small screen with integrity intact. As the 20th anniversary of the Lonesome Dove miniseries approaches this February, we recognize it not only as the most successful miniseries of all time; we celebrate it as the first time anyone got the story right.

The seventh floor of the Albert B. Alkek Library on the Texas State University-San Marcos campus may seem like an unlikely destination for a pilgrimage, yet the devoted journey here from around the globe. They come to the Lonesome Dove room to view relics from a time and place that, if not quite sacred, is revered as an authentic expression of friendship, honor, and the hardships of the Old West as it really was.

Upon entering the room, visitors may feel like Call ticking through the journey in his mind at the end of the film. It’s a hell of a vision. The Hat Creek Cattle Company sign is prominently displayed, and is flanked by mannequins wearing the costumes of Augustus “Gus” McCrae and Woodrow F. Call, two former Texas Rangers who set out on one last adventure to establish the first cattle operation in Montana. Jake Spoon’s bandanna still contains traces of trail dust, and you can almost smell the despair in Lorena Wood’s much-distressed dress. Gus’ Colt Dragoon revolver is nearby, along with the arrows that killed him. The prop that was used for his body is a somber reminder of what was lost along the way, as is the cross from his grave and Deets’ headstone.

“It’s unusual to have so much documentation and memorabilia from a production,” says Steve Davis, assistant curator of the collection. “It’s a great example of how some of the magic of filmmaking is achieved.”

Davis says he’s seen visitors tear up at the site of Gus’ body, a few who have come dressed as Gus and Call, and one who even named his children after the two characters. More than a few people make the Lonesome Dove room their first stop on a journey to retrace the cattle drive route from Texas to Montana. Some do it on horseback.

“It’s heartwarming to work here and see the enormous number of people who come here—who make a pilgrimage, really— to be a part of the Lonesome Dove experience,” Davis says. “The reaction is the same from people from all over the world. There’s a common thread that unites—certainly people from Texas and the West feel that finally a Western told what it was really like. The film has struck a real chord in the American psyche.”

Tommy Lee Jones and Robert Duvall in Lonesome DoveLonesome Dove began as a movie idea dreamed up by Larry McMurtry. In 1972, McMurtry wrote a screenplay treatment titled Streets of Laredo to star John Wayne, Henry Fonda, and James Stewart. Peter Bogdanovich was to direct. When the project failed to gain traction, McMurtry expanded the story into a long, multi-layered novel. Published in 1985, the book grabbed the imagination of critics and the public alike, spending 20 weeks atop the New York Times best-seller list and winning the Pulitzer Prize for fiction.

“Streets of Laredo didn’t move forward because John Wayne wouldn’t do it,” McMurtry says. “He would have been the Call character in that story, and he didn’t want to play what he considered to be an unlikable, hard-ass character. When he wouldn’t do it, everyone else lost interest. I do have a family background that involved the cattle trade and trail drive tradition, which is probably the main reason I decided to write Lonesome Dove.”

Shortly before the novel’s publication, McMurtry sent a draft to Suzanne de Passe at Motown Productions. Motown optioned the film rights for $50,000 and CBS contracted to air Lonesome Dove as an eight-hour miniseries in four installments. All that remained was to find a way to adapt McMurtry’s sweeping novel for television. That’s when de Passe called on Bill Wittliff to write the screenplay. A Texas native like McMurtry, Wittliff felt a personal connection to the characters and events detailed in the novel.

“Like everybody I thought it was an astonishing piece of work,” Wittliff says. “From a personal response it was so much about my country, my people, but of course everybody felt that. That’s one of the great things about [the novel] Lonesome Dove, everybody identified with it, and I absolutely did.”

Wittliff , who was also co-executive producer with de Passe on the miniseries, wrote most of the screenplay during stints at his vacation home on South Padre Island. He would listen to the book on tape on the 6 1/2-hour drive from his home in Austin.

“What was wonderful about that is that I was driving, not writing, and as I was listening I was making the pictures in my head. I got to see the whole film, or my version of it, making those trips down to South Padre. I would stay a week or so and write, and then I’d drive back and that would be another 6 1/2 hours.”

From the beginning, Wittliff knew that in order for the miniseries to be a success, he had to remain true to the book, and include all of its interconnected threads and characters.

“It’s an epic story, and I never would have left out those subplots,” Wittliff says. “They just gave it the richness and the size. There were some things that we filmed that did not make it to the final edit because we just didn’t have time, but we squeezed in as much as we could.”

“Gus was my favorite character to play.”

— Robert Duvall

Even though the time schedule was almost as tight as the budget, it was soon apparent that the Lonesome Dove project was buoyed by an enthusiasm unlike anything in television. The buzz reached every corner of the industry.

“It’s Larry’s story that got ’em,” Wittliff says. “All the old clichés are true—like attracts in kind. It was a great book, it was a good script, and it attracted great artists. They were so taken by Larry’s novel. I mean we had people from all over the United States who drove in on their own nickel just to see if they could be extras. It wasn’t so much they wanted to get something out of it, they wanted to put something in.”

Diane Lane, who played Lorena Wood, remembers picking up on that feeling as soon as she arrived in Austin to begin filming. “Even the people I met at the airport and the people who did the driving were all so meticulously into each character,” she says. “I’d never seen anything like it.”

That groundswell of intense appreciation for McMurtry’s novel, published just a few years earlier, permeated every aspect of the miniseries.

“There was a reverence for the original material that was carried out by Bill in his writing of the screenplay,” Lane says. “There was also great care taken in the casting, and when [Robert Duvall] signed on everybody couldn’t wait to work with him, so we had top drawer people from the very get-go wanting to play every part.”

Tommy Lee Jones

“Every day was a complete joy. There’s a book called Crying for Daylight about Texas ranching culture, and that’s pretty much how we felt. You’d wake up early crying for daylight so you could get to work.”

— Tommy Lee Jones

Tommy Lee Jones, who played Call, says that the feeling among cast members was that the whole of Lonesome Dove was greater than the sum of its parts. “Everybody that worked on the film cared a great deal about the authenticity of it. They felt it was mainly their responsibility to do right by the book,” Jones says. “There was a social conscience at work that was unusual at that time in the world of television.”

Says Wittliff : “Everybody was absolutely dedicated to it. Nobody ever said ‘oh don’t worry about it, it’s just television.’ We knew it was television, but everybody’s attitude was ‘well, we’re making a huge, epic movie which as it happens is going to be shown on television.”

Epic is right. Shot over 16 weeks at three different locations, the project called for 89 speaking parts, as many as 600 head of cattle, 90 horses, and four sets of pigs. The conditions varied from 100-degree heat on set in Del Rio, Texas, where the fictional town of Lonesome Dove was constructed, to freezing rain and snow in Angel Fire, New Mexico.

The remote shooting locations, budget and time crunch, as well as the sheer scope of the project required an effort far beyond the pale of an average television shoot.

Lane recalls slogging through creeks with a wary eye out for cottonmouths, as well as finding a scorpion in her petticoat while filming the scene where Gus entices her into the river.

“It got larger than life, definitely larger than the scale of normal filmmaking,” Lane says. “But to be in the environs that the story takes place in was very affecting.”

Anjelica Houston and Robert Duvall

“I think it’s one of the best Westerns ever made. It’s about the land, men, women, animals, love, death, the American Dream, freedom, cruelty, fear, survival. And cowboys seem to love Clara.”

— Anjelica Huston

“I came in during the last three weeks and everyone was exhausted, having been in Texas and up in Angel Fire,” says Anjelica Huston, who played Clara Allen. “On several occasions I had to rally the troops because I could see the pages disappearing from the script—we simply did not have the time to do everything.”

But the motivation to bring the novel to life with the upmost authenticity, as well as the camaraderie of the cast and crew, overshadowed the numerous challenges.

We always said Lonesome Dove is the star, and I think everybody felt that,” Wittliff says. “Every once in a while the movie god just points through the clouds and says ‘regardless of what you do, this one’s going to work.’ There were so many places where this one could have fallen off the table. We were inventive in several places, but I don’t think any place cheated the film.”

Extraordinary luck also favored the production, such as when a freak snowstorm hit the community of Angel Fire in the middle of summer—on the same day the script called for a blizzard.

“We had snow machines and everything else ready to go and we woke up and the whole world was white,” Wittliff says. “Let me tell you, stuff like that happened all the time. The whole thing was like walking through a miracle.”

Diane Lane

“I was swayed into that relationship [with Robert Duvall in character as Gus] whether we were on camera or off in terms of our banter and cajoling around.”

— Diane Lane

The first installment of Lonesome Dove aired on Sunday, February 5, 1989. That day blasts of arctic air blew down from Canada and seized most of the country in its icy grip. Many people hunkered down in their homes to wait out the cold, and more than a few tuned in to CBS at 9 p.m. to watch Gus McCrae and Woodrow Call begin their adventure. Those who weren’t watching received a call from a friend or family member during the commercial breaks telling them to turn it on.

“Everybody stayed home and they started watching Lonesome Dove, and of course once you started then you couldn’t quit,” Wittliff says. “It was just unbelievable. People forget, at the time we did it the only thing deader than Westerns were miniseries, and this was a Western miniseries.”

Lonesome Dove generated huge ratings for CBS, and the network aired the miniseries for a second time shortly thereafter. Lonesome Dove won seven Emmys and two Golden Globes that year, but the public response was even more telling.

“It was overwhelming—the reviews were all great and the mail from people all across the country poured into the office,” Jones says. “We got heartfelt letters by the sack full from people who recognized their granddads and their fathers and their uncles in the story. They’d usually seen movies that were labeled ‘Western,’ and this seemed to defy that stereotype and be about real people and real places. They were very grateful to see the reality of their own history as opposed to some commercial distortion.”

Diane Lane

“The dialogue, the characters, the individualism of the people, the self-sufficiency, the ruggedness, it was all captured so well in Lonesome Dove,” says Ricky Schroder, who played Newt Dobbs. “It depicts a piece of our history as Americans that speaks to us. I think we all like to think about a time when life was simpler, when there was more black and white instead of gray.”

In many ways, Lonesome Dove also set a new benchmark for the way Westerns looked and felt. Says costume designer Van Broughton Ramsey: “I think that’s one of the reasons why we’re all still so proud of it 20 years later. Lonesome Dove was one of the first films to really show that the Old West is not about shoot ’em up, it’s about facing the everyday problems in life, being thankful for what you have, and moving on the best way you know how.”

It’s that simple, universal message, as well as the realistic portrayal of humanity in all its extremes, that keeps Lonesome Dove a fan favorite 20 years after its original release. And why, despite a lack of modern special effects and fast-paced sizzle, the film continues to resonate with a new generation of viewers.

“I wish Robert Urich [who played Jake Spoon] was still with us so he could experience the gratitude from all of the fans for his work,” says Lane. “But the wonderful gift of film is that the grave has no sway. You are forever in that encapsulated bubble and that’s a brilliant gift that film gives back to people who work in that medium. Your work can live forever.”

About the Photos

The photographs in this article were taken by Bill Wittliff during the production of Lonesome Dove. They are part of the Wittliff Collections at Texas State University-San Marcos, which Wittliff founded with his wife, Sally, in 1985. The photos are also collected in A Book of Photographs from Lonesome Dove published in 2007 by the University of Texas Press.

A Book of Photographs from Lonesome Dove

http://thewittliffcollections.txstate.edu/spec-coll/ldbook.htm

Oliver Loving to Governor Lubbock, 1862

Oliver Loving was a pioneering cattle driver. During the Civil War he drove cattle from Texas to feed Confederate forces along the Mississippi River, a service that left him in enormous debt when the war ended. In this letter, Loving proposes to raise several companies of men to make war on the Indians. In later years, Loving and Charles Goodnight became famous for their cattle drives from Texas to Santa Fe. Loving was killed by Indians in 1867 while on the trail. The character of Augustus McCrae in Larry McMurtry's classic novel Lonesome Dove was partially based on his life.

Charles Goodight

Charles Goodnight (March 5, 1836 – December 12, 1929) was a cattle rancher in the American West. He was born in Macoupin County, Illinois, the fourth child of Charles and Charlotte (Collier) Goodnight. He moved to Texas in 1846 with his mother and stepfather, Hiram Daugherty. In 1856, he became a cowboy and served with the local militia, fighting against Comanche raiders. A year later, in 1857, Goodnight joined the Texas Rangers. At the outbreak of the Civil War, he joined the Confederacy. Most of his time was spent as part of a frontier regiment guarding against raids by Indians. Following the war, he became involved in the herding of feral Texas Longhorn cattle northward from West Texas to railroads. In 1866, he and Oliver Loving drove their first herd of cattle northward along what would become known as the Goodnight-Loving Trail. Goodnight invented the chuckwagon, which was first used on this cattle drive.

On July 26, 1870, Goodnight married Mary Ann (Molly) Dyer, a schoolteacher from Weatherford, Texas. Goodnight developed a practical sidesaddle for his wife to use.

In 1876, Goodnight founded what was to become the JA Ranch in Palo Duro Canyon.

Charles Goodnight statue outside of the Panhandle-Plains Historical Museum at the West Texas A&M University campus.In addition to raising cattle, Goodnight preserved a herd of native American Bison, which survives to this day. He also crossbred buffalo with domestic cattle, which he called cattalo.

Goodnight became sick after his wife's death in April of 1926, but was nursed back to health by Corinne Goodnight, a 26 year old nurse and telegraph operator from Butte, Montana, with whom Charles had been corresponding because of their shared surname.

In his last years he mined in Mexico and tried to become a movie producer. On March 5, 1927, Charles turned 91 and married the very young Corinne Goodnight. Goodnight died on December 12. 1929, in Phoenix, Arizona.

Named after Goodnight are Charles Goodnight Memorial Trail, the Panhandle town of Goodnight, Texas, (former site of the Goodnight Baptist College and birthplace in 1920 of the renowned scientist Cullen M. Crain), several streets in the Panhandle, and the highway to Palo Duro Canyon State Park. Goodnight is also known for guiding Texas Rangers to the Indian camp where Cynthia Ann Parker was recaptured, and for later making a treaty with her son, Quanah Parker.

Larry McMurtry based the relationship between Gus McCrae and Woodrow Call on the relationship between Goodnight and Loving, in his Pulitzer Prize winning novel "Lonesome Dove" and its sequels. The grave marker Call carves for one of the characters late in the novel is based on an actual gravestone Charlie Goodnight had created, and the trek back to Texas at the end of the novel is based on Goodnight's return of Loving's body to Texas. There are other notable influences from Goodnight's life in the novel as well.

All four novels include brief appearances by Goodnight, and he plays his largest role in the final (chronological) volume of the series, Streets of Laredo. Charles Goodnight is very famous around Canyon and Amarillo, Texas. Goodnight also appears briefly in the prequel Dead Man's Walk and in a more prominent role in the sequel Streets of Laredo, where he and Call have become good friends. Goodnight is played in the film by James Gammon. The Western novelist Matt Braun's novel Texas Empire is based on the life of Goodnight and fictionalizes the founding of the JA Ranch.

On July 26, 1870, Goodnight married Mary Ann (Molly) Dyer, a schoolteacher from Weatherford, Texas. Goodnight developed a practical sidesaddle for his wife to use.

In 1876, Goodnight founded what was to become the JA Ranch in Palo Duro Canyon.

Charles Goodnight statue outside of the Panhandle-Plains Historical Museum at the West Texas A&M University campus.In addition to raising cattle, Goodnight preserved a herd of native American Bison, which survives to this day. He also crossbred buffalo with domestic cattle, which he called cattalo.

Goodnight became sick after his wife's death in April of 1926, but was nursed back to health by Corinne Goodnight, a 26 year old nurse and telegraph operator from Butte, Montana, with whom Charles had been corresponding because of their shared surname.

In his last years he mined in Mexico and tried to become a movie producer. On March 5, 1927, Charles turned 91 and married the very young Corinne Goodnight. Goodnight died on December 12. 1929, in Phoenix, Arizona.

Named after Goodnight are Charles Goodnight Memorial Trail, the Panhandle town of Goodnight, Texas, (former site of the Goodnight Baptist College and birthplace in 1920 of the renowned scientist Cullen M. Crain), several streets in the Panhandle, and the highway to Palo Duro Canyon State Park. Goodnight is also known for guiding Texas Rangers to the Indian camp where Cynthia Ann Parker was recaptured, and for later making a treaty with her son, Quanah Parker.

Larry McMurtry based the relationship between Gus McCrae and Woodrow Call on the relationship between Goodnight and Loving, in his Pulitzer Prize winning novel "Lonesome Dove" and its sequels. The grave marker Call carves for one of the characters late in the novel is based on an actual gravestone Charlie Goodnight had created, and the trek back to Texas at the end of the novel is based on Goodnight's return of Loving's body to Texas. There are other notable influences from Goodnight's life in the novel as well.

All four novels include brief appearances by Goodnight, and he plays his largest role in the final (chronological) volume of the series, Streets of Laredo. Charles Goodnight is very famous around Canyon and Amarillo, Texas. Goodnight also appears briefly in the prequel Dead Man's Walk and in a more prominent role in the sequel Streets of Laredo, where he and Call have become good friends. Goodnight is played in the film by James Gammon. The Western novelist Matt Braun's novel Texas Empire is based on the life of Goodnight and fictionalizes the founding of the JA Ranch.

The African-American character of Deets in "Lonesome Dove" is based on a real black cowboy, one of many who worked for Charles Goodnight and Oliver Loving over the years.

Bose Ikard was born a slave and went West to work for Oliver Loving in 1866. He worked for Charles Goodnight and Oliver Loving when they were partners. When Loving died, he remained a steadfast friend and employee to Charles Goodnight.

Following his work in the cattle drives, Ikard settled in Weatherford, Texas. He and his wife, Angeline, were the parents of six children. He died in 1929 at age 85. Goodnight had a granite marker erected at his grave.

Goodnight wrote about Ikard:

"Bose surpassed any man I had in endurance and stamina. There was a dignity, a cleanliness and reliability about him that was wonderful. His behavior was very good in a fight and he was probably the most devoted man to me that I ever knew. I have trusted him farther than any man. He was my banker, my detective, and everything else in Colorado, New Mexico and the other wild country. The nearest and only bank was in Denver, and when we carried money, I gave it to Bose, for a thief would never think of robbing him: Bose Ikard served with me four years on the Goodnight-Loving Trail, never shirked a duty or disobeyed an order, rode with me in many stampedes, participated in three engagements with Comanches, splendid behavior. ... Bose could be trusted farther than any living man I know."

Goodnight was responsible for saving one of the few remaining buffalo herds. He and his wife developed a passion for the animals. One of the loves of his life was cross-breeding cattle and buffalo and getting "cataloes." Charlie also created a wildlife sanctuary that replaced his passion for cattle drives in his later years.

The definitive work about Charles Goodnight was written by J. E. Haley: "Charles Goodnight, Cowman and Plainsman," 1942. The tales in that book were later the basis for such Western classics as "The Searchers," "Red River," "Sons of Katie Elder" and, of course, "Lonesome Dove."

Actor Barry Corbin lives in Texas. A fan of Western history, particularly Texas history, Corbin put together a one-man show a few years ago. It depicts Charles Goodnight on the last day of his life.

Corbin described Charles Goodnight: "In any part that you do, there is an honesty to your character and you have to get in touch with that. In the case of Goodnight, it's easy because his core of honesty extended all the way out to surface."

"Charlie Goodnight's Last Night" is a microcosm of an era marked by loyalty and devotion to personal codes. "What is important today about Charles Goodnight is the man's unshakable belief in right and wrong," says Corbin. "He lived by a code, which most people on the frontier did. And that's almost unheard [of] today."

Bose Ikard was born a slave and went West to work for Oliver Loving in 1866. He worked for Charles Goodnight and Oliver Loving when they were partners. When Loving died, he remained a steadfast friend and employee to Charles Goodnight.

Following his work in the cattle drives, Ikard settled in Weatherford, Texas. He and his wife, Angeline, were the parents of six children. He died in 1929 at age 85. Goodnight had a granite marker erected at his grave.

Goodnight wrote about Ikard:

"Bose surpassed any man I had in endurance and stamina. There was a dignity, a cleanliness and reliability about him that was wonderful. His behavior was very good in a fight and he was probably the most devoted man to me that I ever knew. I have trusted him farther than any man. He was my banker, my detective, and everything else in Colorado, New Mexico and the other wild country. The nearest and only bank was in Denver, and when we carried money, I gave it to Bose, for a thief would never think of robbing him: Bose Ikard served with me four years on the Goodnight-Loving Trail, never shirked a duty or disobeyed an order, rode with me in many stampedes, participated in three engagements with Comanches, splendid behavior. ... Bose could be trusted farther than any living man I know."

Goodnight was responsible for saving one of the few remaining buffalo herds. He and his wife developed a passion for the animals. One of the loves of his life was cross-breeding cattle and buffalo and getting "cataloes." Charlie also created a wildlife sanctuary that replaced his passion for cattle drives in his later years.

The definitive work about Charles Goodnight was written by J. E. Haley: "Charles Goodnight, Cowman and Plainsman," 1942. The tales in that book were later the basis for such Western classics as "The Searchers," "Red River," "Sons of Katie Elder" and, of course, "Lonesome Dove."

Actor Barry Corbin lives in Texas. A fan of Western history, particularly Texas history, Corbin put together a one-man show a few years ago. It depicts Charles Goodnight on the last day of his life.

Corbin described Charles Goodnight: "In any part that you do, there is an honesty to your character and you have to get in touch with that. In the case of Goodnight, it's easy because his core of honesty extended all the way out to surface."

"Charlie Goodnight's Last Night" is a microcosm of an era marked by loyalty and devotion to personal codes. "What is important today about Charles Goodnight is the man's unshakable belief in right and wrong," says Corbin. "He lived by a code, which most people on the frontier did. And that's almost unheard [of] today."

cabin

Goodnight Barn: Pueblo, Colorado (CO)

Loving's Bend

By Edgar Beecher Bronson in 1910

From San Antonio to Fort Griffin, [Texas] Oliver* Loving was a name to conjure with in the middle sixties. His tragic story is still told and retold around campfires on the Plains.

One of the thriftiest of the pioneer cow-hunters, he was the first to realize that if he would profit by the fruits of his labor he must push out to the north in search of a market for his cattle. The Indian agencies and mining camps of northern New Mexico and Colorado, and the Mormon settlements of Utah, were the first markets to attract attention. The problem of reaching them seemed almost hopeless of solution. Immediately to the north of them the country was trackless and practically unknown. The only thing certain about it was that it swarmed with hostile Indians. What were the conditions as to water and grass, two prime essentials to moving herds, no one knew.

To be sure, the old overland mail road to El Paso, Chihuahua, and Los Angeles led out west from the head of the Concho to the Pecos; and once on the Pecos [River], which they knew had its source indefinitely in the north, a practicable route to market should be possible.

But the trouble was to reach the Pecos [River] across the ninety intervening miles of waterless plateau called the Llano Estacado, or Staked Plain. This plain was christened by the early Spanish explorers who, looking out across its vast stretches, could note no landmark, and left behind them driven stakes to guide their return. An elevated tableland averaging about one hundred miles wide and extending four hundred miles north and south, it presents, approaching anywhere from the east or the west, an endless line of sharply escarped bluffs from one hundred to two hundred feet high that with their buttresses and re-entrant angles look at a distance like the walls of an enormous fortified town. And indeed it possesses riches well worth fortifying.

While without a single surface spring or stream from Devil's River in the south to Yellow House Cañon in the north, this great mesa is nevertheless the source of the entire stream system of central and south Texas. Absorbing thirstily every drop of moisture that falls upon its surface, from its deep bosom pours a vitalizing flood that makes fertile and has enriched an empire, --a flood without which Texas, now producing one-third of the cotton grown in the United States, would be an arid waste. Bountiful to the south and east, it is niggardly elsewhere, and only two small springs, Grierson and Mescalero, escape from its western escarpment.

A driven herd normally travels only twelve to seventeen miles a day, and even less than this in the early Spring when herds usually are started. It therefore seemed a desperate undertaking to enter upon the ninety-mile "dry drive," from the head of the Concho to the Horsehead Crossing of the Pecos, wherein two-thirds of one's cattle were likely to perish for want of water.

Oliver Loving was the first man to venture it, and he succeeded. He traversed the Plain, fought his way up the Pecos, reached a good market, and returned home in the Autumn, bringing a load of gold and stories of hungry markets in the north that meant fortunes for Texas ranchmen. This was in 1866. It was the beginning of the great "Texas trail drive," which during the next twenty years poured six million cattle into the plains and mountains of the Northwest. Of this great industrial movement, Oliver Loving was the pioneer.

At this time Fort Sumner, [New Mexico], situated on the Pecos about four hundred miles above Horsehead Crossing, was a large Government post, and the agency of the Navajo Indians, or such of them as were not on the war-path. Here, on his drive in the Summer of 1867, Loving made a contract for the delivery at the post the ensuing season of two herds of beeves. His partner in this contract was Charles Goodnight, later for many years the proprietor of the Palo Duro ranch in the [Texas] Panhandle.

Loving and Goodnight were young then; they had helped to repel many a Comanche assault upon the settlements, had participated in many a bloody raid of reprisal, had more than once from the slight shelter of a buffalo-wallow successfully defended their lives, and so they entered upon their work with little thought of disaster.

Beginning their round-up early in March as soon as green grass began to rise, selecting and cutting out cattle of fit age and condition, by the end of the month they reached the head of the Concho with two herds, each numbering about two thousand head. Loving was in charge of one herd and Goodnight of the other.

Each outfit was composed of eight picked cowboys, well drilled in the rude school of the Plains, a "horse wrangler," and a cook. To each rider was assigned a mount of five horses, and the loose horses were driven with the herd by day and guarded by the "horse wrangler" by night. The cook drove a team of six small Spanish mules hitched to a mess wagon. In the wagon were carried provisions, consisting principally of bacon and jerked beef, flour, beans, and coffee; the men's blankets and "war sacks," and the simple cooking equipment. Beneath the wagon was always swung a "rawhide"--a dried, untanned, unscraped cow's hide, fastened by its four corners beneath the wagon bed. This rawhide served a double purpose: first, as a carryall for odds and ends; and second, as furnishing repair material for saddles and wagons. In it were carried pots and kettles, extra horseshoes, farriers' tools, and firewood; for often long journeys had to be made across country which did not furnish enough fuel to boil a pot of coffee. On the sides of the wagon, outside the wagon box, were securely lashed the two great water barrels, each supplied with a spigot, which are indispensable in trail driving. Where, as in this instance, exceptionally long dry drives were to be made other water kegs were carried in the wagons.

Such wagons were rude affairs, great prairie schooners, hooded in canvas to keep out the rain. Some of them were miracles of patchwork, racked and strained and broken till scarcely a sound bit of iron or wood remained, but, all splinted and bound with strips of the cowboy's indispensable rawhide, they wobbled crazily along, with many a shriek and groan, threatening every moment to collapse, but always holding together until some extraordinary accident required the application of new rawhide bandages. I have no doubt there are wagons of this sort in use in Texas to-day that went over the trail in 1868.

The men need little description, for the cowboy type has been made familiar by Buffalo Bill's most truthful exhibitions of plains life.

Lean, wiry, bronzed men, their legs cased in leather chaparejos, with small boots, high heels, and great spurs, they were, despite their loose, slouchy seat, the best rough-riders in the world.

Cowboy character is not well understood. Its most distinguishing trait was absolute fidelity. As long as he liked you well enough to take your pay and eat your grub, you could, except in very rare instances, rely implicitly upon his faithfulness and honesty. To be sure, if he got the least idea he was being misused he might begin throwing lead at you out of the business end of a gun at any time; but so long as he liked you, he was just as ready with his weapons in your defense, no matter what the odds or who the enemy. Another characteristic trait was his profound respect for womanhood. I never heard of a cowboy insulting a woman, and I don't believe any real cowboy ever did.

Men whose nightly talk around the campfire is of home and "mammy" are apt to be a pretty good sort. And yet another quality for which he was remarkable was his patient, uncomplaining endurance of a life of hardship and privation equaled only among seafarers. Drenched by rain or bitten by snow, scorched by heat or stiffened by cold, he passed it all off with a jest. Of a bitterly cold night he might casually remark about the quilts that composed his bed: "These here durned huldys ain't much thicker 'n hen skin!" Or of a hot night: "Reckon ole mammy must 'a stuffed a hull bale of cotton inter this yere ole huldy." Or in a pouring rain: "'Pears like ole Mahster's got a durned fool idee we'uns is web-footed." Or in a driving snow storm: "Ef ole Mahster had to git rid o' this yere damn cold stuff, he might 'a dumped it on fellers what 's got more firewood handy."

Vices? Well, such as the cowboy had, some one who loves him less will have to describe. Perhaps he was a bit too frolicsome in town, and too quick to settle a trifling dispute with weapons; but these things were inevitable results of the life he led.

In driving a herd over a known trail where water and grass are abundant, an experienced trail boss conforms the movement of his herd as near as possible to the habit of wild cattle on the range. At dawn the herd rises from the bed ground and is "drifted" or grazed, without pushing, in the desired direction. By nine or ten o'clock they have eaten their fill, and then they are "strung out on the trail" to water. They step out smartly, two men--one at either side--"pointing" the leaders; and "swing" riders along the sides push in the flanks, until the herd is strung out for a mile or more, a narrow, bright, parti-colored ribbon of moving color winding over the dark green of hill and plain. In this way they easily march off six to nine miles by noon. When they reach water they are scattered along the stream, drink their fill and lie down. Dinner is then eaten, and the boys not on herd doze in the shade of the wagon, until, a little after two o'clock, the herd rise of their own accord and move away, guided by the riders.

Rather less distance is made in the afternoon. At twilight the herd is rounded up into a close circular compact mass and "bedded down" for the night; the first relief of the night guard riding slowly round, singing softly and turning back stragglers. If properly grazed, in less than a half-hour the herd is quiet and at rest; and, barring an occasional wild or hungry beast trying to steal away into the darkness, so they lie till dawn unless stampeded by some untoward incident.

Every two or three hours a new "relief" is called and the night guard changed. Round and round all night ride the guards, jingling their spurs and droning some low monotonous song, recounting through endless stanzas the fearless deeds of some frontier hero, or humming some love ditty rather too passionate for gentle ears.

But when a ninety-mile drive across the Staked Plain is to be done, all this easy system is changed. In order to make the journey at all the pace must be forced to the utmost, and the cattle kept on their legs and moving as long as they can stand.

Therefore, when Loving and Goodnight reached the head of the Concho, two full days' rest were taken to recuperate the "drags," or weaker cattle. Then, late one afternoon, after the herd had been well grazed and watered, the water barrels and kegs filled, the herd was thrown on the trail and driven away into the west, without halt or rest, throughout the night.

Thus, driving in the cool of the night and of the early morning and late evening, resting through the heat of midday when travel would be most exhausting, the herd was pushed on westward for three nights and four days.

On these dry drives the horses suffer most, for every rider is forced, in his necessary daily work, to cover many times the distance traveled by the herd, and therefore the horses, doing the heaviest work, are refreshed by an occasional sip of the precious contents of the water barrels--as long as it lasts. By night of the second day of this drive every drop of water is consumed, and thereafter, with tongues parched and swollen by the clouds of dust raised by the moving multitude, thin, drawn, and famished for water, men, horses, and cattle push madly ahead.

Come at last within fifteen miles of the Pecos, even the leaders, the strongest of the herd, are staggering along with dull eyes and drooping heads, apparently ready to fall in their tracks. Suddenly the whole appearance of the cattle changes; heads are eagerly raised, ears pricked up, eyes brighten; the leaders step briskly forward and break into a trot. Cow-hunters say they smell the water. Perhaps they do, or perhaps it is the last desperate struggle for existence. Anyway, the tide is resistless. Nothing can check them, and four men gallop in the lead to control and handle them as much as possible when they reach the stream. Behind, the weaker cattle follow at the best pace they can. In this way over the last stage a single herd is strung out over a length of four or five miles.

Great care is needed when the stream is reached to turn them in at easy waterings, for in their maddened state they would bowl over one another down a bluff of any height; and they often do so, for men and horses are almost equally wild to reach the water, and indifferent how they get there.

However, the Pecos was reached and the herds watered with comparatively small losses, and both Loving's and Goodnight's outfits lay at rest for three days to recuperate at Horsehead Crossing. Then the drive up the wide, level valley of the Pecos was begun, through thickets of tornilla and mesquite, horses and cattle grazing belly-deep in the tall, juicy zacaton.The perils of the Llano Estacado were behind them, but they were now in the domain of the Comanche and in hourly danger of ambush or open attack. They found a great deal of Indian "sign," their trails and camps; but the "sign" was ten days or two weeks old, which left ground for hope that the war parties might be out on raids in the east or south. After traveling four days up the Pecos without encountering any fresh "sign," they concluded that the Indians were off on some foray; therefore it was decided that Loving might with reasonable safety proceed ahead of the herds to make arrangements at Fort Sumner for their delivery, provided he traveled only by night, and lay in concealment during the day.

In Loving's outfit were two brothers, Jim and Bill Scott, who had accompanied his two previous Pecos drives, and were his most experienced and trusted men. He chose Jim Scott for his companion on the dash through to Fort Sumner.

When dark came, Loving mounted a favorite mule, and Jim his best horse; then, each well armed with a Henry rifle and two six-shooters, with a brief "So long, boys!" to Goodnight and the men, they trotted off up the trail. Riding rapidly all night, they hid themselves just before dawn in the rough hills below Pope's Crossing, ate a snack, and then slept undisturbed till nightfall. As soon as it was good dusk they slipped down a ravine to the river, watered their mounts, and resumed the trail to the north. This night also was uneventful, except that they rode into, and roused, a great herd of sleeping buffalo, which ran thundering away over the Plain.

Dawn came upon them riding through a level country about fifteen miles below the present town of Carlsbad, without cover of any sort to serve for their concealment through the day. They therefore decided to push on to the hills above the mouth of Dark Cañon. Here was their mistake. Had they ridden a mile or two to the west of the trail and dismounted before daylight, they probably would not have been discovered. It was madness for two men to travel by day in that country, whether fresh sign had been seen or not. But, anxious to reach a hiding place where both might venture to sleep through the day, they pressed on up the trail. And they paid dearly the penalty of their foolhardiness.

Other riders were out that morning, riders with eyes keen as a hawk's, eyes that never rested for a moment, eyes set in heads cunning as foxes and cruel as wolves. A war party of Comanches was out and on the move early, and, as is the crafty Indian custom, was riding out of sight in the narrow valley below the well-rounded hills that lined the river.

But while they hid themselves, their scouts were out far ahead, creeping along just beneath the edge of the Plain, scanning keenly its broad stretches, alert for quarry. And they soon found it.

Loving and Jim were in sight!

To be sure they were only two specks in the distance, but the trained eyes of these savage sleuths quickly made them out as horsemen, and white men.

Halting for the main war party to come up, they held a brief council of war, which decided that the attack should be delivered two or three miles farther up the river, where the trail swerved in to within a few hundred yards of the stream. So the scouts mounted, and the war party jogged leisurely northward and took stand opposite the bend in the trail.

Comanche warriorsOn came Loving and Jim, unwarned and unsuspecting, their animals jaded from the long night's ride. They reached the bend. And just as Jim, pointing to a low round hill a quarter of a mile to the west of them, remarked, "Thar'd be a blame good place to stan' off a bunch o' Injuns," they were startled by the sound of thundering hoofs off on their right to the east. Looking quickly round they saw a sight to make the bravest tremble.

Racing up out of the valley and out upon them, barely four hundred yards away, came a band of forty or fifty Comanche warriors, crouching low on their horses' withers, madly plying quirt and heel to urge their mounts to their utmost speed.

Their own animals worn out, escape by running was hopeless. Cover must be sought where a stand could be made, so they whirled about and spurred away for the hill Jim had noted. Their pace was slow at the best. The Indians were gaining at every jump and had opened fire, and before half the distance to the hill was covered a ball broke Loving's thigh and killed his mule. As the mule pitched over dead, providentially he fell on the bank of a buffalo-wallow--a circular depression in the prairie two or three feet deep and eight or ten feet in diameter, made by buffalo wallowing in a muddy pool during the rains.

Instantly Jim sprang to the ground, gave his bridle to Loving, who lay helpless under his horse, and turned and poured a stream of lead out of his Henry rifle that bowled over two Comanches, knocked down one horse, and stopped the charge.

While the Indians temporarily drew back out of range, Jim pulled Loving from beneath his fallen mule, and, using his neckerchief, applied a tourniquet to the wounded leg which abated the hemorrhage, and then placed him in as easy a position as possible within the shelter of the wallow, and behind the fallen carcass of the mule. Then Jim led his own horse to the opposite bank of the wallow, drew his bowie knife and cut the poor beast's throat: they were in for a fight to the death, and, outnumbered twenty to one, must have breastworks. As the horse fell on the low bank and Jim dropped down behind him, Loving called out cheerily:

"Reckon we're all right now, Jim, and can down half o' them before they get us. Hell! Here they come again!"

A brief "Bet yer life, ole man. We'll make 'em settle now," was the only reply.Stripped naked to their waist-cloths and moccasins, with faces painted black and bronze, bodies striped with vermilion, with curling buffalo horns and streaming eagle feathers for their war bonnets, no warriors ever presented a more ferocious appearance than these charging Comanches. Their horses, too, were naked except for the bridle and a hair rope loosely knotted round the barrel over the withers.

On they came at top speed until within range, when with that wonderful dexterity no other race has quite equaled, each pushed his bent right knee into the slack of the hair rope, seized bridle and horse's mane in the left hand, curled his left heel tightly into the horse's flank, and dropped down on the animal's right side, leaving only a hand and a foot in view from the left. Then, breaking the line of their charge, the whole band began to race round Loving's entrenchment in single file, firing beneath their horses' necks and gradually drawing nearer as they circled.

Loving and Jim wasted no lead. Lying low behind their breastworks until the enemy were well within range, they opened a fire that knocked over six horses and wounded three Indians. Balls and arrows were flying all about them, but, well sheltered, they remained untouched. The fire was too hot for the Comanches and they again withdrew.

Twice again during the day the Indians tried the same tactics with no better result. Later they tried sharp shooting at long range, to which Loving and Jim did not even reply. At last, late in the afternoon, they resorted to the desperate measure of a direct charge, hoping to ride over and shoot down the two white men. Up they came at a dead run five or six abreast, the front rank firing as they ran. But, badly exposed in their own persons, the fire from the buffalo-wallow made such havoc in their front ranks that the savage column swerved, broke, and retreated.

Night shut down. Loving and Jim ate the few biscuits they had baked and some raw bacon. Then they counseled with one another. Their thirst was so great, it was agreed they must have water at any cost. They knew the Indians were unlikely to attempt another attack until dawn, and so they decided to attempt to reach the stream shortly after midnight. Although it was scarcely more than fifteen hundred yards, that was a terrible journey for Loving. Compelled to crawl noiselessly to avoid alarming the enemy, Jim could give him little assistance. But going slowly, dragging his shattered leg behind him without a murmur, Loving followed Jim, and they reached the river safely and drank.

It was now necessary to find new cover. For long distances the banks of the Pecos are nearly perpendicular, and ten to twenty feet high. At flood the swift current cuts deep holes and recesses in these banks. Prowling along the margin of the stream, Jim found one of these recesses wide enough to hold them both, and deep enough to afford good

defense against a fire from the opposite shore, Above them the bank rose straight for twenty feet. Thus they could not be attacked by firing, except from the other side of the river; and while the stream was only thirty yards wide, the opposite bank afforded no shelter for the enemy.

In the gray dawn the Indians crept in on the first entrenchment and sprang inside the breastworks with upraised weapons, only to find it deserted. However, the trail of Loving's dragging leg was plain, and they followed it down to the river, where, coming unexpectedly in range of the new defenses, two of their number were killed outright.

Throughout the day they exhausted every device of their savage cunning to dislodge Loving, but without avail. They soon found the opposite bank too exposed and dangerous for attack from that direction. Burning brush dropped from above failed to lodge before the recess, as they had hoped it might. The position seemed impregnable, so they surrounded the spot, resolved to starve the white men out.

Loving and Jim had leisure to discuss their situation. Loving was losing strength from his wound. They had no food but a little raw bacon. Without relief they must inevitably be starved out. It was therefore agreed that Jim should try to reach Goodnight and bring aid. It was a forlorn hope, but the only one. The herds must be at least sixty miles back down the trail. Jim was reluctant to leave, but Loving urged it as the only chance.

As soon as it was dark, Jim removed all but his under-clothing, hung his boots round his neck, slid softly into the river, and floated and swam down stream for more than a quarter of a mile. Then he crept out on the bank. On the way he had lost his boots, which more than doubled the difficulty and hardship of his journey. Still he struck bravely out for the trail, through cactus and over stones. He traveled all night, rested a few hours in the morning, resumed his tramp in the afternoon, and continued it well-nigh through the second night.

Near morning, famished and weak, with feet raw and bleeding, totally unable to go farther, Jim lay down in a rocky recess two or three hundred yards from the trail, and went to sleep.

It chanced that the two outfits lay camped scarcely a mile farther down the trail. At dawn they were again en route, and both passed Jim without rousing or discovering him. Then a strange thing happened. Three or four horses had strayed away from the "horse wrangler" during the night, and Jim's brother Bill was left behind to hunt them. Circling for their trail, he found and followed it, followed it until it brought him almost upon the figure of a prostrate man, nearly naked, bleeding, and apparently dead. Dismounting and turning the body over, Bill was startled to find it to be his brother Jim. With great difficulty Jim was roused; he was then helped to mount Bill's horse, and hurried on to overtake the outfit. Coffee and a little food revived him so that he could tell his story.

Neither danger nor property was considered where help was needed, in those days. Goodnight instantly ordered six men to shift saddles to their strongest horses, left the outfits to get on as best they might, and spurred away with his little band to his partner's relief.

Loving had a close call the day after Jim left. The Comanches had other plans to carry out, or perhaps they were grown impatient. In any event, they crossed the river and raced up and down the bluff, firing beneath their horses' necks. It was a miracle Loving was not hit; but, lying low and watching his chance, he returned such a destructive fire that the Comanches were forced to draw off. The afternoon passed without alarm. As a matter of fact, the remaining Comanches had given up the siege as too dear a bargain, and had struck off southwest toward Guadalupe Peak.

When night came, Loving grew alarmed over his situation. Jim might be taken and killed. Then no chance would remain for him where he lay. He must escape through the Indians and try to reach the trail at the crossing in the big bend four miles north. Here his own outfits might reach him in time. Therefore, he started early in the night, dragged himself painfully up the bluff, and reached the plain. He might have lain down by the trail near by; but supposing the Comanches still about, he set himself the task of reaching the big bend.

Starving, weak from loss of blood, his shattered thigh compelling him to crawl, words cannot describe the horror of this journey. But he succeeded. Love of life carried him through. And so, late the next afternoon, the afternoon of the day Goodnight started to his relief, Loving reached the crossing, lay down beneath a mesquite bush near the trail, and fell into a swoon. Ever since, this spot has been known as Loving's Bend. It is half a mile below the present town of Carlsbad.

At dusk of the evening on which Loving reached the ford, a large party of Mexican freighters, traveling south from Fort Sumner to Fort Stockton, arrived and pitched their camp near where he lay But Loving did not hear them. He was far into the dark valley and within the very shadow of Death. Help must come to him; he could not go to it.

Luckily it came.

While some were unharnessing the teams, others wert out to fetch firewood. In the darkness one Mexican, thinking he saw a big mesquite root, seized it and gave a tug. It was Loving's leg. Startled and frightened, the Mexican yelled to his mates:

"Que vienen, hombres! Que vienen por el amor de Dios! Aqui esta un muerto."

Others came quickly, but it was not a dead man they found, as their mate had called. Dragged from under the mesquite and carried to the fire, Loving was found still breathing. The spark of life was very low, however, and the mescal given him as a stimulant did not serve to rouse him from his stupor. But the next morning, rested somewhat from his terrible hardships and strengthened by more mescal, he was able to take some food and tell his story. The Mexicans bathed and dressed his wound as well as they could, and promised to remain in camp until his friends should come up.

Before noon Goodnight and his six men galloped in. They had reached his entrenchment that morning, guided by the Indian sign around about it, and had discovered and followed his trail. Goodnight hired a party of the Mexicans to take one of their carretas and convey Loving through to Fort Sumner. With the Fort still more than two hundred

miles away, there was small hope he could survive the journey, but it must be tried. A rude hammock was improvised and slung beneath the canvas cover of the carreta, and, placed within it, Loving was made as comfortable as possible. After a nine days' forced march, made chiefly by night, the Mexicans brought their crazy old carreta safely into the post.

While with rest and food Loving had been gaining in strength, the heat and the lack of proper care were telling badly on his wound. Goodnight had returned to the outfits, and, after staying with them a week, he had brought them through as far as the Rio Penasco without further mishap. Then placing the two herds in charge of the Scott brothers, he himself made a forced ride that brought him into Sumner only one day behind Loving.